![]()

Martin is nearing the end of his expat stint in Singapore and needs to name a successor to take over the country manager role soon. He’s got Thomas in mind – a fellow Dutchman and close friend. They’ve shared a long career history in the company, not to mention many a beer and tennis game! He knows Thomas would love Singapore – and enjoy the spicy food and interesting client challenges. When he discussed this with Tina, his counterpart in Hong Kong, Tina asked him why he wasn’t considering Li Shan. Li Shan led a huge and complicated deal flawlessly last month, and Tina knows that Martin and Li Shan work well together. Martin seemed to hesitate, and then said “Li Shan’s great – she is dependable, so detail-oriented and really good at her job. But I’m not sure if she’s got the enterprise view for this role…it really needs global strategic thinking you know?” Tina says, “Well, how do you know Thomas has that? Moreover, Li Shan’s ambitious – with a bit of coaching and shadowing you, I think she’d be ready. She already has a great client network here…”

Martin frowned – “I do coach her you know – she is very quiet in calls, and even when she speaks up, it’s hard for some people in Amsterdam to understand her. I don’t think she’s ready, Tina. But Thomas – I mean, he’s already got the confidence we are looking for, plus the big bosses back in Amsterdam know him. He’s a safe bet, you know?”

Is Martin right? Why or why not? What is he missing out by not considering Tina’s suggestions? What will it take for a Li Shan to progress – versus a Thomas – in this organization? This is probably not the only such story of its kind. For those of you who work in Asia especially – these conversations are probably too common.

This article provides a glimpse into a few potential factors that might have caused Martin to make these assumptions about Li Shan – and indeed, that might be causing global organizations to be overlooking Asian leadership talent in very real ways.

For many global organizations that are operating in Asia, the talent agenda does not match the business growth agenda. All too often, in such organizations, local Asian leaders are overlooked when it comes to truly global, strategic, enterprise roles, whether in their local markets or on the global stage. According to a McKinsey study, Asia is on track to surpass 50% of the world’s GDP by 2040 by which time it would account for 40% of the world’s total consumption. This economic shift makes Asia increasingly relevant and difficult to ignore. Overlooking Asian talent can result in:

Global strategy risk:

Not having Asian representation in leadership positions and in global roles to articulate the commercial potential in Asia and to bring in diverse cultural views to the global leadership team is a risk for the global business strategy in terms of missed market opportunities, customer connects and innovation.

Local business risk:

YSC research found that 80% of leaders from Asia have the required potential for such roles, and 25% are ready immediately to take the roles, but still, the majority of those hired are from outside the country – expatriates or even non-Asian leaders from the country. This presents a risk for Asian business units because the local leadership teams do not represent their customer base and therefore might lose customers to local competitors.

Talent risk:

When emerging Asian leaders don’t see home-grown role models, don’t receive appropriate developmental opportunities and don’t benefit from local sponsorship, they receive the message that they don’t have a future in the company, thus impacting their engagement and retention.

When we refer to Asian Leaders, we recognise that this is not one single homogeneous group. It includes leaders from a long list of countries like Japan, South Korea, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, India among others. The leaders from these regions are as vast, diverse and unique as the individual countries themselves and their cultures. Despite using the term ‘Asian Leaders’ as a unifying category to symbolise some of the shared challenges and experiences, we urge greater nuance and sensitivity when understanding and engaging with these leaders.

There is a growing realization – especially since the onset of the pandemic – that all of this needs to change urgently. The fact that mobility and relocation have become more difficult has created a greater need to appoint local leaders. At the same time, virtual working has opened up possibilities for Asian leaders to have global roles and be located anywhere in the world. The opportunity for inclusion of Asian talent in the local and the global pipeline has never been clearer. But for many organizations, the numbers still show a blocked talent pipeline for Asian leaders, both in Asia and particularly outside Asia.

To understand this block better, we delved deep into our database of tens of thousands of leaders globally to find differences in capability between Asian leaders and their global counterparts that would explain the low levels of representation. In addition, we interviewed over 25 large scale global organizations across mining, pharmaceuticals, consumer goods, FMCG and beverages both at the regional level and with their global headquarters. Through these, we understood these patterns in a deeper manner and identified some systemic and cultural issues that could explain the gap. At the heart of this phenomenon is a set of beliefs about Asian leaders that might be rooted in a mix of myth and reality. Let us examine four such sets of beliefs – dissecting them into the nuances of how much myth and how much reality they’re based on.

Doers or Shapers?

Assumption:

“Asian leaders are ‘doers’ and not ‘shapers’, they are strong operationally, but not very strategic”

Reality:

YSC data shows no difference in strategic thinking as a leadership capability between Asian and non-Asian leaders. However, Asian leaders are literally and figuratively, often placed far from the global HQ and far from the decision-making power center. When it comes to translating the global strategy to a local one, and the need to influence global stakeholders, leaders like Li Shan face a structural and historically created cross-cultural influencing gap, not a thinking style gap.

Competence or Confidence?

Assumption:

“Asian leaders are less confident to speak up and be assertive”

Reality:

YSC data shows no difference in levels of confidence between Asian and non-Asian leaders. Different styles may be incorrectly interpreted as differences in capability. Being assertive can be perceived as aggressive in Asian contexts, unlike the West, where assertive leaders are seen as confident and effective. There is a known Western bias that advantages extraverted leaders to introverted ones. Quiet, firm, collaborative styles might be more effective in interdependent, collectivist cultures – and thus Asian leaders like Li Shan in fact might have an edge.

Lack of readiness or Lack of fair measurement?

Assumption:

“Asian leaders are less ‘ready’ to assume broader leadership positions than their global counterparts”

Reality:

Based on our industry-leading JDI Model of Leadership Potential™, we found no difference in leadership potential scores. However, many organizations, we discovered, did not use a clearly defined measure for potential. Typically promotion decisions are made based on senior leadership recommendations, which are prone to the inherent bias of promoting those who are ‘similar to me,’ like Martin’s preference for Thomas.

Language or Communication?

Assumption:

“Asian leaders have inadequate communication skills”; “Asian leaders have weaker influencing skills – they focus on harmony and avoid confrontation”

Reality:

This assumption is partly true, but only inasmuch as we define ‘communication’ as ‘English language skills’. English language fluency can unfairly play a disproportionate role in perceptions of capability on the global stage. Asian leaders can benefit from exposure to global projects, global executive leaders and stretch assignments that would help them practice their language skills as well as the experience to not let language diffidence affect their confidence. Global Western leaders can, likewise, benefit from greater exposure to different accents and language training so that they can converse better with employees, clients and leaders beyond their own comfort zone. Similarly, global leaders must realize that influencing can occur in a variety of ways – some leaders might influence through relationships and persuasion, others through strength of conviction alone. Examining Asian leaders’ relationships with their teams and clients gives better insight into their leadership than over-indexing on their English language skills.

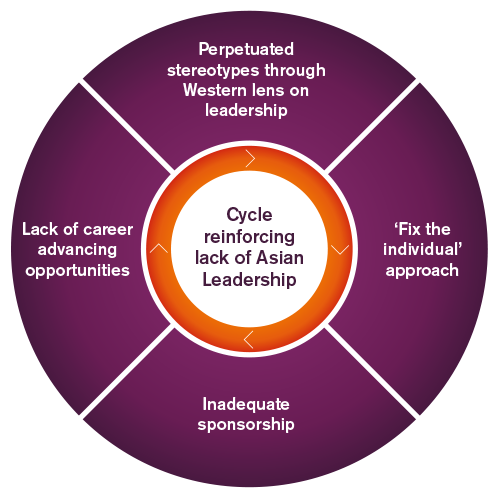

With all four sets of beliefs, the common thread is that the expectations or standards of excellence are centered on a narrow definition that is not truly global – that of the typical White, Western, English-speaking, ambitious and driven masculine model of leadership. This creates a vicious cycle in which local leaders are not seen as ready for developmental opportunities, and thus don’t get the chance to stretch themselves interculturally and develop the influencing skills that would demonstrate their readiness for promotion. It can be harder for Asian leaders to get opportunities to develop and demonstrate senior leadership capabilities, and more costly and risky for organisations to provide them, which ends up in a negative reinforcing cycle. Many global leaders and organizations are not aware of the unfairness that underpins their decision making, nor are they aware of the power and privilege they hold in defining and perpetuating these rigid and outdated standards of performance and leadership. By expanding their definitions and thus, breaking that vicious cycle, global organizations can leverage this opportunity to take Asian leadership truly global.

The only way to break this cycle is to take a systemic view, and start from the top – to increase the global leadership team’s awareness of their role, and the part they play in breaking the cycle. The onus of ‘being ready’ needs to be shared between the local Asian leaders and the global leadership team who can shape the culture and processes to shift the thinking to break that reinforcing cycle.