When was the last time you spoke to your leaders about promoting quality talent based on their performance? Or hiring strong talent that meets your criteria for success and has the experience needed to hit the ground running? In many organizations today, meritocracy is a core principle that underpins decisions around talent and performance, often in the belief that it ensures equal opportunities for growth and development. It is rooted in the principle that the most competent and capable people, get hired and promoted based on their demonstrated effort, achievement and talent. This puts a premium on individual ambition, hard work and perseverance as a vehicle to success – creating a direct relationship between merit and success. What’s more, influenced by COVID-19 and the surge of virtual working, the focus on visible individual inputs has been heightened, posing a greater risk to transparency and the ability to monitor performance and potential consistently and therefore make equitable decisions that impact employees. But what if the playing field from which talent is being assessed, was never level to begin with?

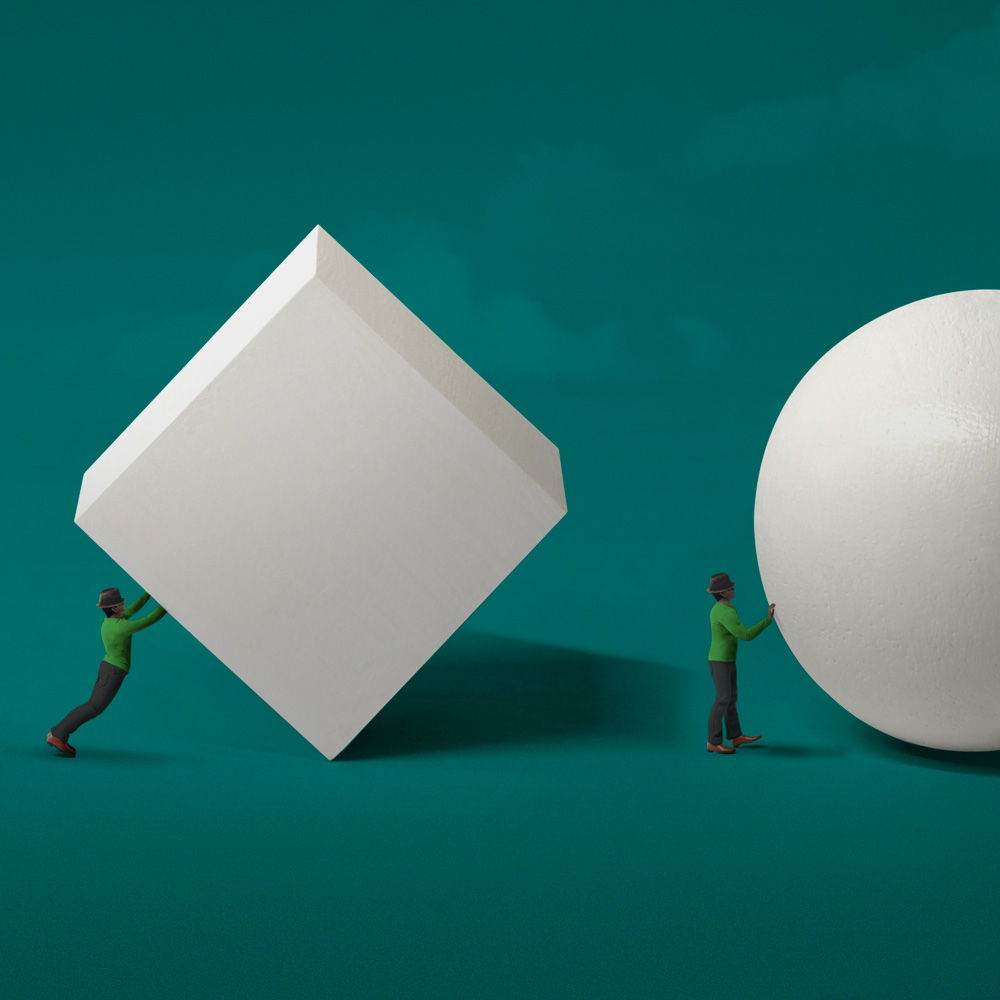

Imagine a group of athletes are running a 100m race. Picture one group running a 100m sprint and the other group running the same race with ‘invisible’ hurdles. The distance and the finish line are identical, and to spectators the outcome (i.e. who crosses the finish line first) is what determines who wins and loses. But in this case, can the finish line really be the marker of achievement? Or might there be other forces at play that enable success? Research shows that there is evidence of disproportionate progression of some groups over others. When you define merit as how quickly you get to the finish line, you ignore the hurdles and obstacles (visible or invisible) that some groups have had to overcome to get there. The key is to recognize that barriers exist for some, and advantages exist for others, which in turn impacts the journey to the outcome.

Sometimes, it’s the start that tends to differ rather than the finish line. When we think about a work context, this takes on a new significance as we track the employee lifecycle. When hiring, recruiters often look for perfect backgrounds, qualifications and strong recommendations from leaders, leveraging social capital. But how often do we recognize those who have demonstrated the determination to succeed despite adversity, through perseverance and grit? It’s the underdog who often gets overlooked and fails to make it past the screening. When we use algorithms to minimize bias and objectively assess candidates, if not careful we can constrain our thinking to the candidates who neatly match the experiences and backgrounds of our existing employee base. This can replicate existing biases and intensity the risk of disadvantage for some groups who might have the requisite experiences but not the traditional skills. Even if these individuals make it into the workplace, the ideal of meritocracy, in the absence of an inclusive culture, can work to further overlook their contributions.

It is widely reported that leaders often hire those who share their attitudes, behaviors, and traits. This propagates a similarity bias and justifies decisions for candidate selection under the guise of ‘job fit’ or ‘culture fit’. Positive biases, although well intentioned can limit the pool of potential candidates for prominent roles, critical projects, and even promotions. When coupled with the illusion of meritocracy, and an absence of a consciously inclusive mindset, leaders can allow these biases to run undetected, and contribute to more systemic inequality within the workplace.

These biases pose barriers that might not be overt, but still limit minority candidates from being hired or promoted into more senior levels. Even when candidates from marginalized groups are hired, in the absence of an inclusive culture, they experience more subtle forms of discrimination such as being excluded from critical discussions, have limited access to decision-makers or mentors/sponsors, and have fragmented relationships with their managers. Taken together, these covert forms of exclusion create blockers for talent, and risk going unobserved in organizations where meritocracy is prided. What’s more, to cope with such discrimination, individuals tone down their differences and even adopt the characteristics of the majority to ‘fit in’. But when employees play down their distinctiveness to merge with the standards of the dominant majority, organizations fail to leverage their unique perspectives and dilute the positive influence of having multiplicity within a team. Thus, meritocracy serves as an invisible screen to maintain the status quo and existing order of the dominant majority and fails to take a critical look at the barriers that can create disproportionate challenges. For leaders looking to tap into the potential of their people, leverage diversity and cultivate inclusive cultures, meritocracy can become an unhelpful barrier, that can stagnate Diversity and Inclusion (D&I) efforts.

But does meritocracy impact how we promote our leaders too? The paradox of meritocracy shows that when a company’s core values emphasized meritocracy, those in managerial positions awarded larger monetary rewards or favorable career outcomes to their male employees, compared to equally performing women employees at the same level. When leaders are focused on meritocracy, it creates the assumption that an objective criteria for merit and hence fairness exists in talent management decisions. However, meritocracy rewards those who are already set up for success and have the scaffolding and resources to have their achievements showcased. When leaders assess their talent only from a meritocratic lens, it reinforces a leader’s sense of impartiality and reduces their awareness of the cognitive biases which can be misconstrued as objective criteria for success. When left undetected, this can trigger larger implications as leaders carry bias forward into talent promotion decisions that impact longer term career development for others.

Whilst the principles of meritocracy are about equality across groups, a deeper look at bias and exclusion points to a more important and often neglected ideal that may be a more suitable alternative – equity. Equity is about acknowledging the unequal starting points and creating processes to ensure that people from marginalized backgrounds can effectively compete, have access to opportunities for development, contribute, and grow, without losing sight of their identities. Often equity is the missing piece of an organization’s D&I agenda which can equalize the ground on which our employees stand. It is what allows us to sharpen our focus to identify the (in)equality of the past that has influenced the present and determine the outcomes that will shape the future.

What can leaders and organizations do to create equitable workplaces?

Redefine the skills needed to be successful in the present and required for the future

Using more objective measures for hiring and development, such as potential identification to supplement existing measures of past performance or experience, will increase the likelihood of identifying the right candidates for the present needs and future success of an organization. Defining the skills required to thrive in the future and looking for candidates who will fulfill them, will mitigate bias and increase the assessment of employees based on their ability to drive both short- and long-term goals. Calibrating assessment decisions with external experts and multiple stakeholders can also help to challenge thinking that negates a preference of a certain ‘type’ of profile.

Look beyond culture fit for employees to augment or add to your culture

We tend to hire employees who will ‘fit in’ but this can be counterintuitive to inclusion efforts. Especially when hiring leaders laterally, look for those who are in sync with the values of the organization but will disrupt the status quo rather than merge into the existing culture. Explore what ‘culture-fit’ really means in your organization and develop objective measures of ‘value-fit’ and ‘culture-add’, to accompany a clear job description, and ensure leaders have what it takes to skillfully nudge the company to achieve its business strategy. This will encourage divergent thinking, bring different perspectives, disruptive viewpoints, and drive potential for change and innovation to unleash a thriving business.

Identify homogeneous pockets and dig deep

Leaders can use people analytics and employee dispersion data to ascertain if there is a particular profile of leader that gets hired or promoted more often than others. Armed with this knowledge, they can explore if the decision-making processes and criteria are inclusive and free from systemic bias and therefore expand the pool of candidates they attract and grow. They can also use this information to leverage data and technology to create algorithms that can drive more objectivity in recruitment, and identify potential in a bias free way. Putting in more robust measures will also enable more specific and actionable performance feedback which cultivates greater trust and transparency within the organization.

Re-evaluate the processes that make up your performance management system

Many organization rely on merit to reward their employees, but research shows that the criteria behind performance evaluation or merit may not always be fair across minority groups. This performance-reward bias is more likely to occur when structural conditions like more discretion, less accountability, and less transparency are present. Monitoring processes and putting in checks around the performance evaluation systems, such as requiring HR approval beyond line manager nomination and using data-driven metrics that measure people related outcomes, will work to counter potentially biased outcomes.

Establish a culture that emphasizes equity today to build a meritocratic tomorrow

Unless we can level the playing field, we will not be able to foster an environment where everyone thrives, including our businesses, customers and communities. To reach this goal, we need to shift mindsets, behaviors and adapt processes to build the foundations for today. Consider how we can build more inclusive cultures: How can we be more curious and open-minded to the diverse opinions around us without dismissing them as disruptive? How can we increase courage and challenge ourselves, others and systems that favor a narrow profile, to prepare for a better future? How can we build connections beyond visible or invisible differences, to create bonds across human systems and empower individual and collective success?